|

We, Me, Them & It: The Return

By Guest Contributor Richard Pelletier, Writer for Business & Associate Partner ar Dark Angels

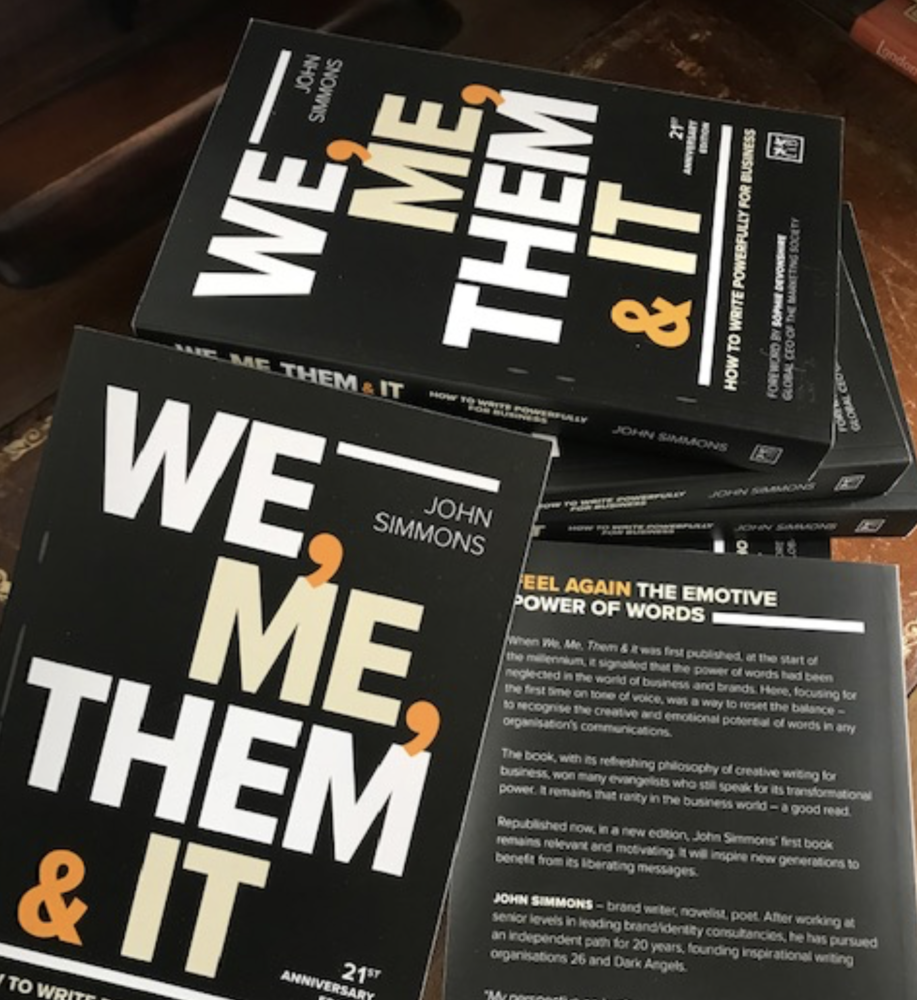

The Paris Vertu’s Richard Gendreau travelled to Washington State to meet with Richard Pelletier to talk about the book that he says changed his life. The interview took place over two stormy days in late March. April 26 is the American launch of We, Me, Them & It, the cult classic by the English writer, John Simmons.

There are no direct flights from anywhere in the world to Clinton, WA. To get there you need to fly into Seattle, where, rumor has it, you should steel yourself for a positively criminal commute north. Or you can fly into tiny Everett, Washington (no direct flights there, either) then Uber over to the ferry dock ten minutes away and hop on a boat. From Paris we flew to San Diego. From there we flew into Everett. Minutes later we stood on the upper deck of the stately Issaquah ferry and felt the salt sea air kissing our tired faces. It was raining.

At our first meeting the next morning at his hideaway cottage on the south end of Whidbey Island, (the fourth largest in the continental US), Pelletier began by complaining. The island’s famous poet ignores him. There’s too much noise from airplanes overhead. (There were none that we could see or hear.) He quickly told us that Alice Munro herself lived in a town called Clinton, although that probably didn’t mean anything.

Within minutes he’d stopped with the poet and the planes. He introduced us to his lovely wife Linda, and made us a perfect Cortado. Then he led the way into his cozy writing shed behind his house. Rumor has it that no one but Linda is ever allowed inside.

The day was unremarkable if 25mph winds (gusting to 60) and torrential rain is unremarkable. Even with the wind singing through the trees, we could hear birdsong, horses neighing in nearby pastures, roosters and frogs. And the rare jet plane. Hanging on the walls of Pelletier’s shed are black and white landscape photographs of his beloved island. One entire wall is given over to books on writing.

One shelf—near the top—is dedicated solely to the books of John Simmons, who Pelletier credits with his success as a writer which at the time of this interview can best be described as epic on the one hand and somewhat difficult to quantify on the other.

We were told that Pelletier can be an especially difficult interview, more prone to complaining and talking about himself, but he could not have been nicer or more generous. Over the course of a two-day visit, we took a few country walks to visit some baby lambs who lived across a grassy field, and to say hey to a few horses in the neighborhood.

An inveterate walker, Pelletier was at his most expressive and expansive when we were plodding down a country road, or navigating a trail through the woods.

RG: Talk about your first encounter with WMT&I. Where were you and how did it happen?

RP: I was living in Baltimore, just a few doors down from the lifelong home of H.L. Mencken, the greatest American prose stylist after Mark Twain. It was early in my writing life and I was looking for a way to move my practice forward. Somewhere there’s a record of my search query, but I’m confident it didn’t say, ‘Copywriting book that swoons over The Admiral Pulaski Skyway, Yeats, Raymond Carver, Dennis Potter, Dancin’ broccoli heads, lost dogs named Lucky, and poetry. If memory serves (and does it ever?) I believe WMT&I popped up due to the misbegotten impulses of Amazon’s suggestion engine. Shall I say more?

RG: Tell us more.

RP: I bought the book on May 17, 2006. The record does show that at the very same time I also ordered How We Die: Reflections on Life’s Final Chapter by Sherwin B. Nuland. My mother had died the previous March, and it appears that in my grief, I was trying to understand what had just happened and what might lie ahead. I wrote a five star review of WMT&I that began, ‘This is not a ‘how to’ book.” I was floored. For the first time in my life I sat down and tried to write a review of a book I’d read. I remember sitting in my back yard in Baltimore at our rickety little blue café table. Even in May, the temperature was 99 degrees and the humidity was the same. The drone of sirens rained down on me like BBs. I had pages and pages of notes, my laptop, and the book. I will tell you that in those sticky moments something exquisite and beautiful and deep had happened to me. I was so moved that I stayed in that chair for days on end and I worked. I’d found something so important to me that it deserved everything I could bring to it. It wouldn’t be crazy to say I had found my life. When I finished I was as proud of that piece as anything I’d ever tackled. I titled it The Empire Writes Back. It landed on the front page of Marketingprofs.com for two solid weeks.

RG: Then what happened?

RP: Everything. New clients, new projects—a whole new life. Beautiful friendships. Lines from that piece ended up in a best selling book on marketing. Lines that veered perilously close to outright theft.

RG: What enchanted you?

RP: Enchanted is precisely the word, Gendreau. Well done. It struck me as eccentric in the best possible way. There was a kind of loose and slightly mad love of language. There was a sense of play. He talked about words giving pleasure. Words could be both medium and material. Words could be mischievous and marvelous.

OR JUST REALLY, REALLY LOUD AND BIG.

or really, really quiet and small.

Words could be so many things, depending. And Simmons was saying that we can—to some degree, if we’re lucky—shape what they do. It’s pretty fantastic that the same communication system that gives us Tread Softly Because You Tread on My Dreams can also give us Your Assistance in Keeping the Aisles Clear of Luggage Would be Appreciated. Which I have to say sounds like a perfectly realized Lydia Davis story. Anyway, back to enchantment. This was my first encounter with tone of voice. And that notion, that a distinct human voice, with a personality, could emerge from inside a business and out to an audience, wow. That was something new and enchanting and pretty wild. I was most appreciative.

RG: In his book, Simmons utilizes various works of literature to make some of his arguments, such as when he cites Seamus Heaney and his translation of Beowulf.

RP: Gendreau, if you ever use the word utilize in my presence again—

RG: Makes use of?

RP: Looks to. Explores. Investigates. As to Seamus. Simmons is never happier than when he’s flashing his Merton College Student ID card. So let’s discuss. This might be the most Simmonsy thing ever. He’s taking a kind of core sample. Or maybe it’s a forensic investigation. Whatever it is, this falls within the Me section of the book and illustrates his thinking. Who are we? Where do we come from? What linguistic stream or tributary or compost pile do any of us draw our words from? Whatever is yours is awesome and wondrous and wicked. Exploit early and often.

RG: I love where he mentions big-voiced scullions.

RP: Exactly. Hold on, let me try something.

Ed note: Pelletier jumped onto his computer and searched for a minute and then read out loud from his screen.

RP: So this is what Simmons does. He lights a torch, and then you’re compelled to follow him down one tunnel after another. So I’ve just googled ‘Seamus Heany – big voiced scullions’. Listen to this from a Dr. Mark Womack.

“So. This is the way Heaney starts the poem, (Beowolf) quelling instantly the long (and tedious) academic debate about how to translate its opening word, Hwæt. He gets “so,” Heaney explains, from his Irish relations, whom he calls, in a previous poem and in the “introduction” to this one, “big voiced Scullions.” Why “big voiced”? Because, “when the men of the family spoke, the words they uttered came across with a weighty directness, phonetic units as separate and defined as the delph platters displayed on a dresser shelf.” In their mouths, a sentence like “we cut the corn today,” says Heaney, “took on immense dignity”; when they opened a statement with “So,” the idiom operated “as an expression that obliterates all previous discourse and narrative, and at the same time functions as an exclamation calling for immediate attention.” Heaney wanted, then, to make Beowulf speakable by one of his Scullion relatives; what he loved about the poem was “a kind of foursquareness about the utterance, a feeling of living inside a constantly indicative mood.”

Is that not beautiful? And so this is the glory of all this—the epic loveliness of our own linguistic traditions, our own voice, and all that it can do. And it was John Simmons—not your average copywriter, right?—who has told us, reminded us, that there are deep connections to be found if you go digging. If you are present for this, miracles can happen.

RG: When did you two meet?

RP: We met at the airport in Seville. I’d flown to Spain—this was 2011—to be at my first Dark Angels workshop. I was told to go to the airport where a flock of writers would be falling out of a Ryanair flight from London. We met, shook hands, and everyone climbed into a van and made the long and winding trek up to a glorious farm house in the mountains. We got in late and were met (and fed) by Stuart Delves one of the original founders of Dark Angels, and Charlotte Halliday, a wonderful writer from Edinburgh. Jaimie Jauncey, another founder, claimed to be in India. We all sat around a big table together in the kitchen and stayed up late. Angus Grundy was there along with Ed Yeoman, Jan Dekker, Rowena Roberts, Sue Evans, Paul Murphy, Richard Casebow. What a time. What a crew. The image I have in my mind is John Simmons reaching over to uncork yet another bottle of red. We talked films, books, music, politics. I remember telling everyone that America was crazy, but not so crazy that we’d ever elect anyone to the presidency as stupid as Michelle Bachman or Sarah Palin. Ha, ha. I thought I’d died and gone to heaven. They gave me a room of my own for having come so far. The wall to wall kindness and joy that prevailed was impossible to miss and has never once lifted in all the years since.

__________________

Hi Richard—

You can most have of the Thursday 22nd in Seville with your wife. You don’t need to get to Sevilla airport until our plane (Ryanair) arrives from London Stansted – due to land at 20.45. If you wait at the exit from the arrivals hall, we should all meet up there.

John

__________________

RG: Getting back to the book. Why do you think it’s had such broad appeal? It hit a nerve in you, but it also landed with a lot of other people. It may have even started its own movement, or community.

RP: Not may have, it did. A lot of copywriters are writers, first and foremost. Lots of copywriters have dreams of being among the beloved and admired creators of memorable poetry, fiction, memoir, and screenplays. Commercial writing pays the rent. Simmons himself is one of these people—and he’s done it. He’s realized his long-held ambition to be a novelist. He’s got three books of fiction on the shelf now, and there’s another one coming. But at the same time it’s an utterly ridiculous dream to be a writer. You have to be more than a little bit demented. You!? Ha! Dream on. But there was John Simmons in so many words, saying, ‘yes, you, and yes, please dream on.’

So for lots of us, the Simmons book, the Simmons thing, is like nectar. We can pay the rent, while we swim with Shakespeare and Goethe and Cervantes and Milton and Carver and Dennis Potter and the advertising stuff, too. And let’s look at what they’ve done because it’s all absolutely amazing, and we can steal some of it for ourselves. Plus, at night after we have done this, we’ll drink and sing, and we’ll swap stories back and forth and we’ll encourage each other and we won’t feel so alone. What book loving copywriter is going to walk away from that? There’s also this thing that James Hilman talks about, the soul’s code. This has to do with one’s calling. And I think for anyone reading his books, you feel that John Simmons has found his calling and that is a profoundly lovely thing to be inside of, right? You can feel his delight, his joy. It’s infectious.

RG: Talk about, ‘There is no such thing as the correct use of language.’

RP: Oh, man. Deep love. I wanted to hunt down every nun who’d ever shamed and tormented me and wave the book in her face. Do you see now?? I think that’s the moment when I thought, huh, he’s a bit of an English radical. I confess I turned that sentence over in my mind for years. But the longer I’ve been writing, the more convinced I am of the truth of it. A simple example. The old saw is to use the active voice over the passive. I think John argues for this to help slay the corporate voice we all know too well. But really? In every instance? I find myself kind of loving the weird spectral presence who’s talking about luggage and clear aisles and appreciation that I mentioned earlier. It’s almost as if the passive voice has been at the party for so long, we’ve all become friends now, and it’s all okay. Oh, it’s you again, hello. The only thing that matters is that meaning be crystal clear. Oh, boy. Here we go.

Right then we heard an explosive crack and then a crash. A tree had come down. The power went out with a loud ‘CLICK’ which Pelletier said happens every time there was a light breeze. He was cursing the local power company as we packed up our stuff and left. We came back at noon the next day—the power had come back around midnight—and we picked things back up.

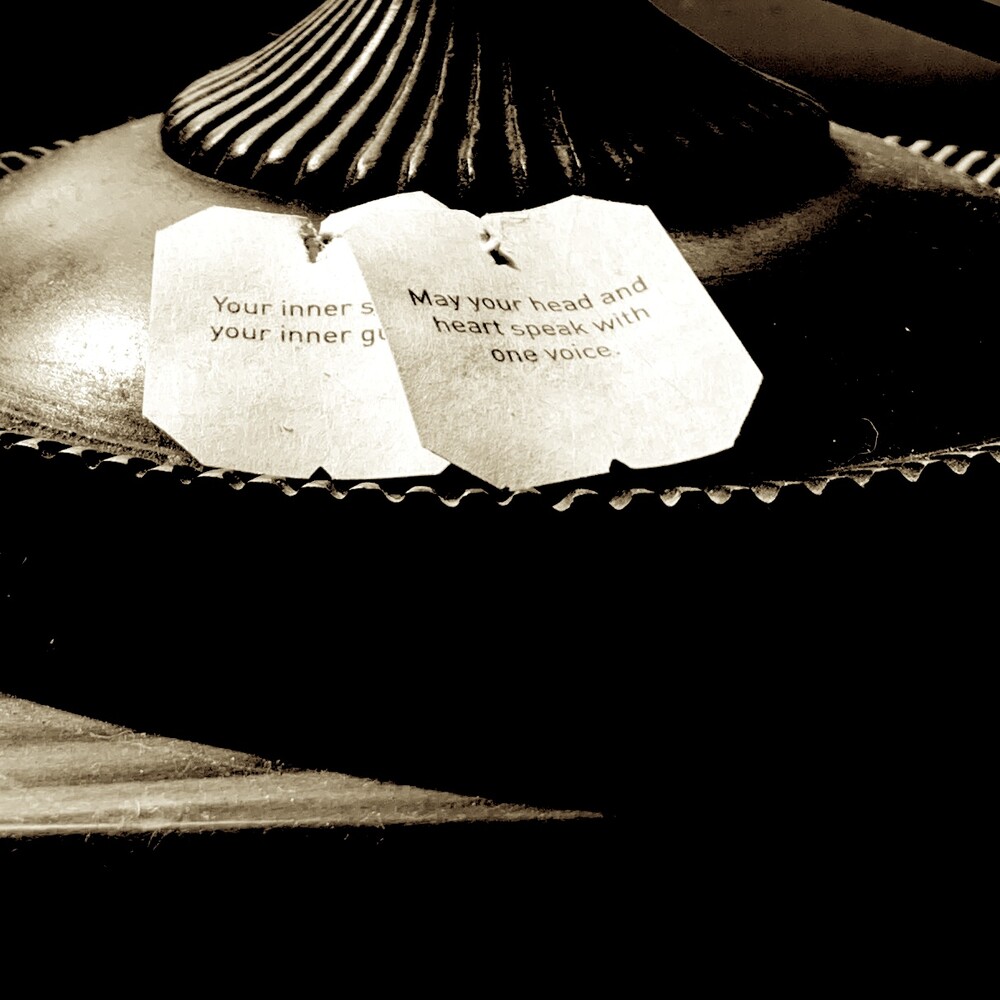

As we arrived the next morning, Pelletier came strolling out of his writing shed (he writes from seven to around ten each day) to say hello. A few minutes later we sipped our cortado’s in the sun-filled kitchen. The storm had headed east. We noticed a couple of teabag tags in his kitchen window. They seemed a perfect way to frame the day’s conversation.

It was breezy but sunny and Pelletier decided that we’d start out with a short walk around the neighborhood and then finish in the shed. For a good long while, we leaned against a metal gate, took in the sun, and talked. Just on the other side of the gate, was Blue—a big beautiful gelding who lives next door. Blue was head down chomping on grass.

RG: You started texting me at five o’clock in the morning. You asked me to remind you about it.

RP: Right. So Deborah Levy is my newest literary crush. A South African born writer raised in England who’s as good on the page as anyone. I am besotted with her non-fiction. I recently heard her talking about her three outstanding memoirs, Things I Don’t Want to Know, The Cost of Living, and Real Estate. She related how she once gave a talk about Cindy Sherman, the extraordinary American photographer. And in that talk, she heard herself speaking in a particular tone of voice that she describes as intimate, formal, and digressive. She used those words. She paid close attention and reached for it when writing her memoirs. So when I hear that story—a story about a great writer’s voice, and how that voice carried an entire narrative and has connected deeply with readers—I can’t help think of John Simmons and how he got so many people thinking about voice. I feel a great big chunk of gratitude.

RG: In WMT&I, Simmons writes a letter to his two children. You don’t see that too often in a business book.

RP: And what a letter. Everyone’s in there. I’d honestly forgotten the passages about John’s brother, Dave. Those passages are incredibly affecting. And lead us right into another story, the one about his aunt Ce, and her relationship to Dave, and then we have his beloved mother Jessie, and her political activism, which we can still see in John even today. Politics was our connecting rod, John’s a bit mad for our crazy American elections. We should note here that with that letter he’s doing the thing he preaches. Bring your self to the work, bring your self to the page. And there’s another gem in there, too.

RG: When he mentions that little boy, Jesus.

RP: My god—an interviewer who has actually read the fucking book. You’re a bit like me, Gendreau. It’s very weird. Anyway, so yes, and this is one of those truly lovely events that can happen in a life. During the Spanish Civil War, John’s parents fostered a young boy from Bilbao. There was a concerted effort to get large numbers of children out of harm’s way and into England (and other places) for the duration of the war. The boy’s family was so grateful, they sent John’s parent’s a desk, which was later used by John’s own children.

But then of course, another thing happens. One night in Spain, John Simmons has a dream. And in the dream come the words, “Mother declared herself happy.” Which became a prologue, which became a very beautiful book, Spanish Crossings. In which a little boy is lifted out of the Spanish Civil War and lands in England. Word of caution: I strongly advise against asking John about all the serendipitous events that happened around that book. You do not have that kind of time—no one does.

RG: How would you describe John Simmons’ tone of voice?

RP: Hmm…You had to ask that one. So focusing on this book only. Let’s remember that he’s an Englishman. And to my American ears, he sounds very English. But also not, because he’s pretty clean and direct. Not quite as direct as an American voice, but his arrow is pointed straight ahead. The clarity is pin prick sharp. The logic flows, the structure is there. We expect this from someone like him, with his experience. But the balance is striking because he’s both teaching and he’s not teaching. If you were a corporate writer who spent your days leveraging low-hanging fruit on a best-in-class, mission critical drill down for maximum impact, and you picked up this book, you would not feel one ounce of shame. And that’s because of the sophisticated way John Simmons tells this story. He is not pedantic.

WMT&I leans as much as it can toward show, don’t tell, which is ridiculously hard to do in a book like this. All of this material is head. These are mostly ideas he’s talking about. But he really wants to talk about heart. In lesser hands this all would become really abstract—humorless academic sludge. But because he started from his heart and simply began by talking about words, the material thing he loves the most, it lands. It reassures and so it endures.

“This book is about recognizing that words are living things. Because we are human we know that we should care about other living things. Most of the time we do not. We let them starve through neglect. We step over them when we see them on the street trying to attract our attention. We pull the curtains so we don’t have to look at them. We even lock the doors on them if we feel they threaten us.” ~ John Simmons

Read that paragraph. Then read it again. That paragraph is deeply political and is doing a lot of work. That is the voice of a humanist. Someone who is advocating for an honest and open and ethical relationship between humans—and between humans and the words they choose to live with all day and night. We need this now more than ever.

RG: There’s even Arsenal. And the Labour Party.

RP: Yes. There is no way on this earth that John Simmons writes any book on any topic whatsoever and does not get Arsenal and Labour onto the page somehow. Hell would freeze over first.

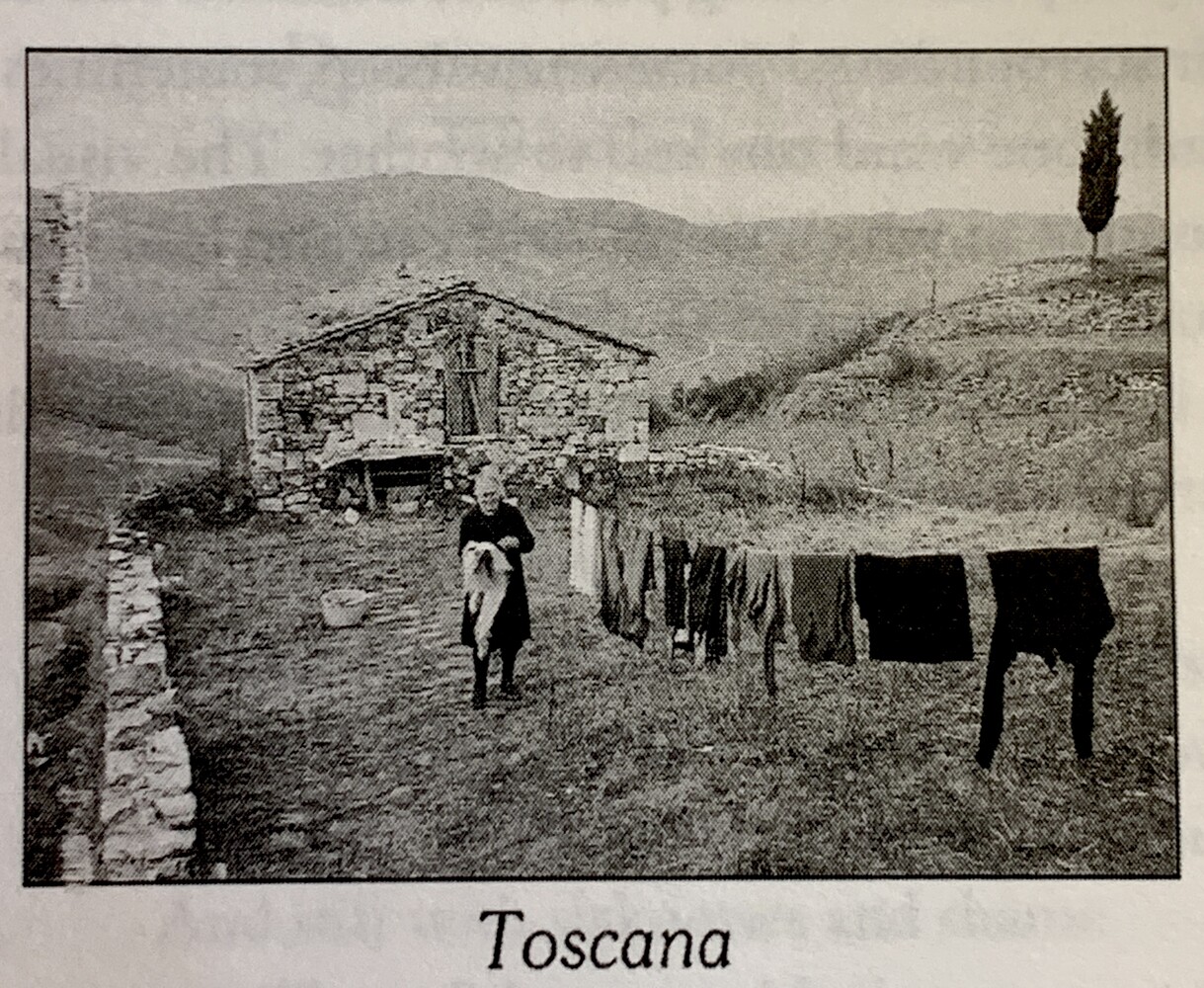

RG: In the last section, It, he talks about combining text and images. There’s a postcard with a message on the back. That’s an interest of yours, no?

RP: Good catch. I’d forgotten. Years before I read WMT&I, I used to make little postcards of my own photographs and write stories on the back. A very close friend of mine has kept a small collection of them. It’s so curious, for years I zigged and zagged around my own interest in words and images. It’s an obsession now. But you’re right, it’s literally right there in John’s little book. Fate calls and sometimes we are there to answer. It’s almost like he was leaving me little breadcrumbs to show the way.

Hey, that thing you like, that thing you’re playing around with…the postcards and the little stories on the back? Keep doing that, keep playing. There’s something real in it.

Dear Matthew and Jessie,

As you can see our villa is simple but adequate. Your mother is happy doing the washing while I sit by the pool but exposure to the sun has aged her a little. She doesn’t mind as long as she has clothes to wash so please send any spares you have to Sienna Post Restante. Enjoying ourselves,

Dad and Mom

The larger point of course is that words can gather up tremendous power in combination with strong images and inspired design. John is extremely fond of good design as any writer should be. Shit.

RG: What?

RP: If he’d left out Post Restante—sestude.

RG: Don’t know what that is. What’s only connect? I’ve heard that’s John’s mantra.

RP: I reached out to John after I’d read his book and published my review. It took a bit of doing to locate him, and connect with him. This was before Twitter. He was kind of enough to write back, although I was a tiny bit miffed because I wanted more than a sentence or two from him. Some time later, I found Jamie Jauncey’s blog by accident. And I could see that these two scoflaws were linked somehow. And I said something like, “I don’t what you two are doing, but I want in.”

As a connector, John is in a category all his own. All this is a long way of saying if you are moved by someone’s book, someone’s art, someone’s talent, someone’s being, connect with them. No one can promise you a whole new life, but do it anyway. We should always and forever tell people what they have meant to us.

So, John Simmons, I’m happy to be telling you again. Your book has changed my life. It’s like a little miracle happened. I can’t quitefigure out a smart way to say how many ways you’ve changed it, but I’ll try. Multitudinous. Multifarious. Myriad. Innumerable. Umpteen. Legion. Gruntload. Motherlode. Shed load. Shitload. Pant load. Shit ton.

Although I could never possibly repay you, please consider these words a token of my appreciation. I am eternally grateful. You wrote one hell of a song. Congratulations.

RG: You told us how you started your review back in the day. You said, ‘This is not a how to book.’ How did you finish it?

RP: At the time, I was really taken with another Brit. A different sort of British explorer. This is Robert Falcon Scott and his spectacularly doomed voyage to the South Pole in 1912. It’s one of the greatest stories ever told. An epic blizzard swirls around Scott as he sits in a tent, dying. He’s actually made it to the South Pole but won’t make it back. His supply depot is only 11 miles off, but he’s too weak to get there.

In his journal, Scott pens a deeply moving letter to his family. Which is sort of like someone we know, right? So to end the piece, I nicked Scott’s words for myself and then I brought my personality to the page.

“It seems a pity,” wrote Scott, “but I do not think I can write more.”

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Richard Pelletier is a writer for business at Lucid Content, Associate Partner ar Dark Angles writers. Richard has worked with some very prestigious brands. Much of his work is web content and case studies, sometimes known as customer success stories.

Suggested Reading

It’s no good having a good idea if you cannot communicate it to someone else. We, Me, Them & It demonstrates how we can write and use words more creatively and persuasively in business today. From differentiating your company from another, to injecting life and vibrancy into your products and services, to writing everyday emails, this cult business book by the modern-day guru of business writing (now released as a new 21stanniversary edition) shows ways in which we can use words to gain competitive advantage in business life through “tone of voice”.